In Conversation with King Britt

February 2024

Pew Fellowship recipient, King James Britt (his real name) is a 30+ year, producer, composer, performer and educator in electronic music. As a composer and producer, his practice has lead to collaborations with the likes of De La Soul, Alarm Will Sound Orchestra, Saul Williams, director Michael Mann (Miami Vice) and many others. He’s a standout performer, from the countless global venues and festivals, to his humble roots as the original DJ for the Grammy Award winning Digable Planets. He is also the creator of UCSD’s Blacktronika lecture course, researching and honoring the people of color, who have pioneered groundbreaking genres within the electronic music landscape. As a legend within the Philly scene, King uses his platform to empower other artists coming up, as well as those who have paved the way for him to do what he does so well. We got together with King, along with Philly native turned rising star, Joshua Lang, to chat about King’s influences, his long standing career, his UCSD course, and much more.

︎

We

sat down with King to chat about his

influences, his long standing career, and his Blacktronika course, alongside Philly native Joshua Lang.

We sat down with King to chat about his influences, his long standing career, and his Blacktronika course, alongside Philly native Joshua Lang.

Coloring Lessons: Peace King! Want to thank you a million for making the time to chat with us.

King Britt: I’m honored to talk to you guys! As I said over email, y’all are taking the torch. In terms of paying respects— and not even in an ego way, because I do it too, but the work y’all do is great and it gives context to everyone new coming into the scene. Especially all the kids who love EDM…

CL: Thank you so much! It’s really our pleasure. We wanted to speak a bit about your life and career— the things that have impacted you and led you on this path. Can you tell us a bit about what growing up in Philly was like and some of your early household memories?

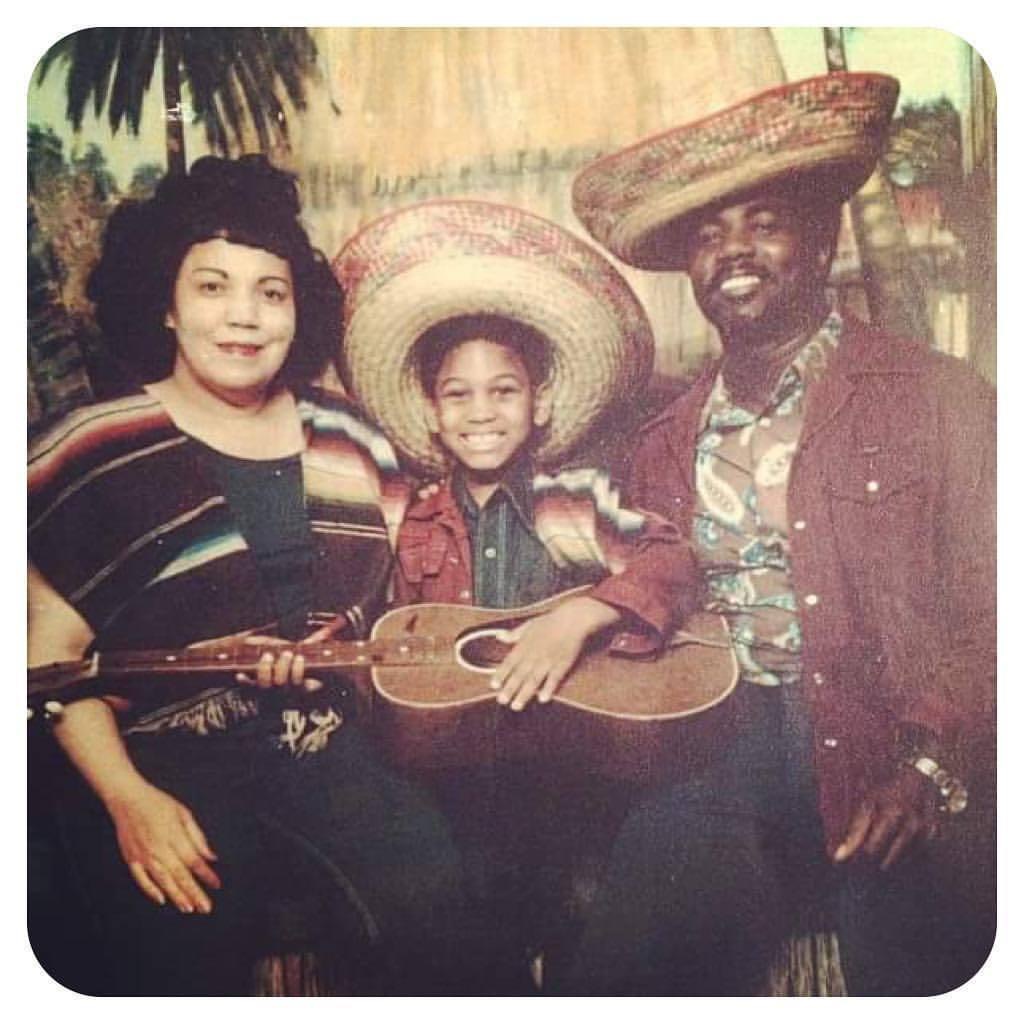

KB: I was in Philly for 50 years. I’ll be 54 in November…I only left four years ago so I’m still very attached. I was born in South West Philly and so the 1970’s were my formative years. My parents were both collectors of music and were always out at shows. They didn’t believe in babysitters so they would take me to these shows with them. This is back when the rules were different and you could get away with taking your kids to the bar or to the club.

One of my earliest memories was seeing James Brown at the Latin Casino in Philly. I was 5 years old, but even then to see James Brown with the full Orchestra I was like “WOAH!”. My dad was a big James Brown fan so I had already known his music, but to experience it live was something else. When my dad was 15, coming from the small town of Campblleton, Florida, he met James Brown on the Chitlin’ circuit and started collecting all this stuff.

CL: ...and your mom?

KB: My dad went into the army young and met my mom at Fort Dix in New Jersey, at a USO club. My mom worked as a nurse, and at the same time worked as a hostess at the USO club (an entertainment club where folks in the army and officers alike would frequent).

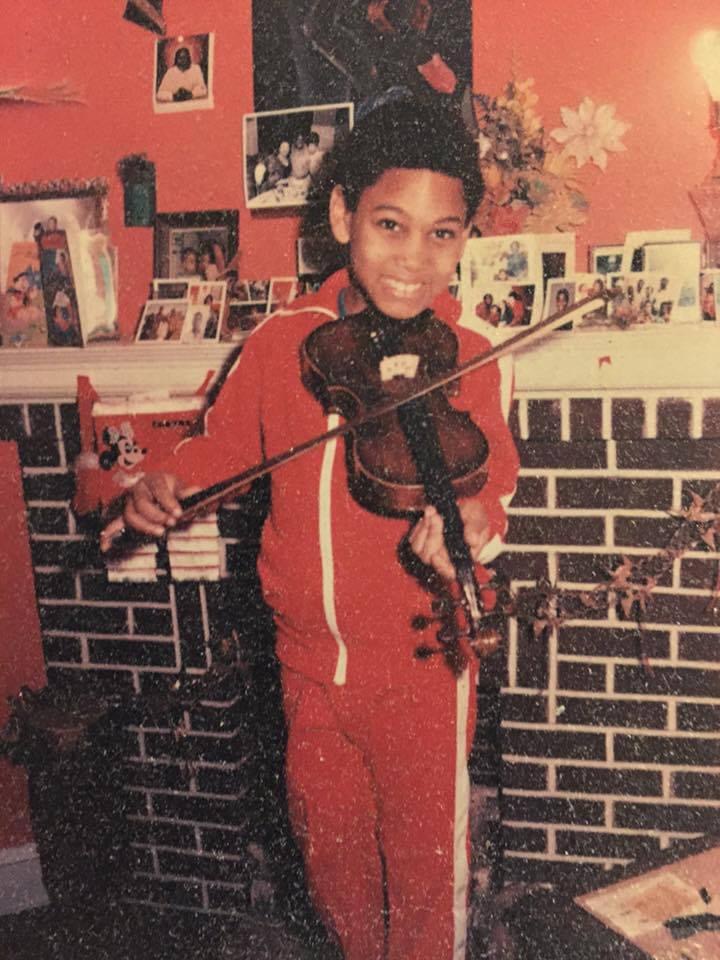

That’s how she came to know all the jazz greats— from Duke Ellington, to Cab Calloway. She would even take me to Sun Ra rehearsals as a child. My mom is a Jazz aficionado and collected all of it…that’s my DNA. Growing up listening to everything from Funk to Spiritual Jazz, with heavy Philadelphia influences. My dad was strictly funk. He owned a barbershop in the 80’s, and at the barbershop my job was to put records on the record player and keep the patrons happy. I think that was the first time I realized the impact music had on people. The way you could change the energy of a room just by playing the right song.

CL: At what age were you in and out of your dad’s barbershop and playing records over there?

KB: It started from around 6 years old to around 11. I didn’t really want to be there— I would’ve rather been outside, riding around on my big wheel. Instead, it was like a 5 year residency at my dad’s barber shop [laughs].

CL: The youngest DJ to hold a residency in Philly [laughs]! Were there any other times you had been actively made aware of the power of music and its effect on people?

KB: So these were still my early formative years, but my parents would always take me to black exploitation films and I was really inspired by those soundtracks. Roy Ayers to Issac Hayes— seeing visuals with that music was really powerful.

At the same time, we had WDAS Radio, which still to this day is probably the best black radio station in Philadelphia, and WHAT Radio which was an AM radio station hosted by Dyana Williams. Dyana Williams was like our ambassador of music— any questions you have about anybody in Philly from the 1960’s all the way up until now, Dyana has that information. Because she had a show, she would get releases and white labels before anyone else, and so we would hear all this music through that channel too. The social commentary from that music really spoke to us. From “I’ll Always Love My Mama” [The Intruders] to “Backstabbers” [The O’Jays]. It was extremely instrumental in the formation of who we are as a generation.

CL: We wanted to ask— when we were young, while we listened to everything our parents played, we also rebelled a bit and got into the more electronic side of music. Did you ever have that experience? Were you listening to anything at that age besides jazz and funk?

KB: Oh yeah! It was Rock music.

CL: How did you get exposed to that?

KB: Okay, so in grade school my mom took me out of our neighborhood and put me into the Greenfield school downtown on Chestnut.

CL: Is it still there?

KB: Still there…still one of the top schools in the city with a 2-3 year waiting list. That school changed my life. The grandmother of James T Taylor (Kool And The Gang) used to drive all of us to school because she lived in West Philly.

Joshua Lang: How old were you at that time?

KB: I was around 12. Right around the time Hip-Hop was becoming huge in Philly. Do you know Charlie Mack?

CL: No, we aren’t familiar.

KB: Ok, so Fresh Prince [Will Smith] and DJ Jazzy Jeff used to do our high school parties at Central High. Of course, this was before the Grammy and the TV show. So when they first started out, if you listen to any of the first albums, they had a line that would go “Charlie Mack, first out the limo!” This was their homie and bodyguard.

He had an Ice Cream shop in Southwest Philly that I would frequent and he would always look out for me. I remember he would always tell me, “You should go see Jazzy Jeff, he’s playing at the YMCA, he’s playing at this party, that party, etc” So when I finally got around to checking Jeff, I heard him playing Billy Squier and Led Zeppelin...but he was playing the breaks. I was blown away. It was Jeff that kind of put it together sonically for me.

CL: So he was able to give those Rock songs context in the Hip-Hop setting?

KB: Context, exactly. I also never really wanted to be a DJ in that scene. I wanted to be a radio host and play the music I wanted.

CL: ...and at the time, the music you wanted to play was still Rock?

KB: Oh yeah. I was loving the rock stuff when I went to high school but only had a few records. I didn’t really dive into the genre before I got into Central High, and around 1982, Central High became co-ed. It was the first time in high school with girls and I had just started making tapes. I was like “oh shit, I can make tapes for girls!”. It was the ice breaker. So it was at that time where I really was diving into the stuff I liked.

One of my close friends at the time was DJ Dozia, and we both had similar musical tastes. Dozia is one of the greats in Philly if you don’t know…and so we started getting into more New Wave stuff, like Depeche Mode and The Smiths. We would go to shows and really get to explore the music first hand.

There was a store in Philly called Up Against The Wall right by Tower Theatre. We’d go to Tower to see the shows, and then go to that store to get the band shirts— the Police, AC/DC, you name it. My mom at the time would see me and be like “PLEASE…Don’t forget your blackness. I respect the style of music you’re listening to, but don’t forget, all that music that you’re listening to came from us.”

CL: Did you believe her at that point?

KB: When my mom got serious and sat you down…yeah, I believed her. Especially coming from the Black Panther background, and her history with that— I definitely believed her. It didn’t mean much because I kept going in that direction musically, but eventually Hip-Hop would find me.

I used to date this girl in 1983, and her sister is the famous Faith Newman. If you don’t know her, I encourage you to look her up. She was one of the first A&R’s for Def Jam in the very beginning of the label’s inception. She even discovered Nas. So Faith would give my her sister these tapes from Def Jam, and one of those tapes was Beastie Boys. We’d listen to those tapes a lot. The thing about them was they combined Punk & Hip-Hop together and it blew my mind. Between Public Enemy, The Bomb Squad, and those early Beastie Boys tapes, I found myself diving straight into Hip-Hop. Rock kind of just fell by the wayside— it was Hip-Hop and drum machines. I even saw a bit of my dad’s style in Herbie Hancock’s Rockit. That was it for me.

CL: Ah, okay. The reason we ask is because it feels like we all have this experience of our parents letting us know where the music came from and whether or not we were at the age or maturity level where we could see that. It’s interesting that part of your early influences was Rock which in a way, opened you up to Hip-Hop…

KB: Just to be clear, the entryway into Hip-Hop was Jazzy Jeff and Fresh Prince, and these parties they used to do around Philly. Hearing the early iterations of DJing and Rapping. There were other DJ/Producers in Philly— Grand Wizard Rasheen & Kid Destroy (better known as graffiti artist, Estro). Kid Destroy was the first to have early drum machines playing under the records, and making these beat tapes before anyone was doing that kind of stuff in Philly. My entryway was that. It was “It’s Yours!” By T La Rock [1984]. That sound plus Run DMC and Jazzy Jeff…a culmination of what was going on in my city played a big part.

That said, there was something about the Beastie Boys, because I loved Rock music. I speak for many alternative black kids when I say this. I remember taking my daughter to AfroPunk and I almost started crying, because we always dreamed of having an event like that when we were younger, celebrating the multiple genres of black music. So the beastie boys were the first group that married the different things that we loved into one package. It wasn’t my entry way, but it definitely resonated with me; in just the same way as Public Enemy did. It definitely changed the way I listened to Hip-Hop.

CL: Was it around high school when you first started getting into production?

KB: So in 1984, I had my first group with my boy Dozia, and the name of the group was Black Celebration.

CL: Was it still the Hip-Hop producers inspiring your work?

KB: We were really influenced by Depeche Mode and anything Vince Clark did, whether it was his solo project Yaz, or the other synth and new wave stuff coming out at that time.

There was a show called Rock Over London, that was broadcasted over Rock Station WMMR Radio in Philly. We would tune in every Friday night to hear all the stuff coming out of London. Then we have a station called WXPN, and they used to play the John Peel show. I’m sure you’re familiar with the name John Peele—

CL: BBC, right?

KB: Exactly. John broke all these new records and presented all these new sounds. So Friday night, we would listen to these shows and get all this New Wave and Ska. We would buy anything that came out of London. We would skip school just to go buy these records, and so our natural inclination was, we needed to get these synthesizers. I worked a summer job and saved up all my money to buy my first Mini Moog.

KB: It was like $5,000 in the store, but because I lived in South West Philly….yeah [laughs]. You know what I mean? Equipment was kind of easy to come by. If you think about New York City and the famous blackout of 1977…right after that blackout you started to hear a lot of DJs come out, and a lot of new music, too. There was so much equipment floating around New York at really good prices. That changed Hip-Hop. Access changes how scenes are created, and the access to turntables, mixers, synthesizers, was more accessible in the hood around that time.

CL: So true! We even read about Roland with the 303 Bass Line Machines and how they had to put it on sale because nobody wanted it at the time.

KB: Yes! I was talking to DJ Pierre in my class, and he said he bought one at the pawn shop for $40.

In Philly, we had a store called Cintolis, and everybody in the city used to go to this guy. His name was Benny, and everything you wanted, he had it. I don’t know where it all came from but he had like 20 Moogs, tons of synthesizers, you name it. He would just pull stuff out of the warehouse and be like “ah, give me $200 for it”.

We also had a mall in Philly called The Gallery. James Poyser [Roots, Erykah Badu, Lauren Hill, etc]— we all came up together. He was working at the Polo store in the mall and we would often talk. I bought one of my first keyboards from him; the Yamaha Dx100.

CL: So you start accumulating all this equipment. What was it that you were making at the time?

KB: We started to make more Synth Pop, with influences like Depeche Mode, Kraftwerk, and Heaven 17. It’s also worth it to mention that although we didn’t know it when we were kids, Francois K changed our lives. Every big record that we loved, Francois touched it. When he became my mentor years later, I would play with him a lot, and to this day we still talk. He’s one of my heroes for sure.

CL: He’s touched everything. Truly a legend.

JL: Speaking of production, were you ever going to Sigma Sound Studios when you first started making music?

KB: Very good question— no I wasn’t. We didn’t have that much money. For those who don’t know Sigma, it was the home of all the Philly International Sound. Bowie, Elton [John], Luther [Vandross]. Everyone at that time wanted that signature Philly sound and Sigma was the space for that, but you had to have a lot of money.

At this time we were just making tapes. We hadn’t even been thinking about the possibility of making music, especially as a career. We were just having fun.

...and then going into college, I went to Temple for marketing. Definitely wasn’t thinking about the studio in that context, until I started working at Tower Records. Tower Records was one of the greatest record stores ever.

CL: You were a buyer there, yes? How did you get that role?

KB: Yeah, I was a buyer. Here’s how it happened. I was a back check guy, before moving to the register. The 12 inch dance buyer got let go and that section was a huge part of the profits. They knew that I knew all the music and releases, and they offered me the buyer’s job. Nice pay raise and I got to travel to places like New York…

CL: …and you were only 18 at the time?

KB: 18 going on 19. It was crazy! A buyer at Tower??? I had an expense account…I got all the promos. This is how I came to know everyone in the scene. Everyone I bring in to Blacktronika from Derrick May, 4Hero and Carl Craig, to DJ Pierre and Richie Hawtin, all these guys I would know because I was buying their records at Tower.

All the DJs were coming into Tower, and at that time, you didn’t have listening stations, so you couldn’t listen to records. You’d have to go solely on my word. This was also where I met my man Josh [Wink].

CL: Josh Wink of Ovum Recordings?

KB: That’s right. We all went to Temple, but I met him through his roommate. He used to come through to Tower, and we hit it off. This was back during the time where I was making demo tapes, and simultaneously Strictly Rhythm and Nervous Records were starting.

I was playing at a place called Revival and I was coming up under the wing of legendary Philly DJ Bobby Startup. I would see him play everything. We’d play back and forth for 12 hours at this after hours party. I was probably getting around $40 a gig with free drinks. The upside was that I was meeting all these people in the industry and because I worked at Tower, there was this synergy within the DJ community.

I had felt like I wanted to play my own music and with these house labels starting in New York, where I felt like I had more access, I thought it might be a good time to put a record out. I had just finished my demo tape of E-Culture. At the time it was a solo project, but once I got the deal I brought Josh [Wink] in. He didn’t know much about production but we just hit it off and the rest is history.

CL: I wanted to briefly ask— You mentioned names like Dego and Goldie. Did you have a big UK dance music influence at this time? Breakbeat & Drum and Bass and that kind of stuff?

KB: Because of Rock Over London in high school, anything out of the UK was super cool to us, whether it be fashion or music.

I got the deal with Strictly Rhythm for our E-Culture project and I’m like Josh, let’s do this. We went to NYC and spent all our money in the studio and we finished that project. His girlfriend rapped on it and it blew up overseas in the UK.

They asked both of us to go over there and spin, but at the time I was working so we couldn’t go together. Josh went first. Once I made it over, it was crazy because I had never played outside of Philly! My boy Dozia went with me and we went to all the London fashion spots, and then to all the record shops. Because I knew all the producers from buying their stuff for Tower, we figured we’d try to meet some of the artists. I called 4Hero’s manager and we went over to the famous Reinforced Records studio in Dollis Hill to meet them. Future Sound of London was in the downstairs studio and this was when the rave scene was at its Apex. “Papua New Guinia” had just blown up, Acid House is huge, 808 State had just come out…

CL: So this was like late 80’s?

KB: 1989. I was geekin’ because I was in England for the first time meeting all these cats. So in the studio, Mark [“Marc Mac” Clair] is at the controls and Dego is hunched over in this small ceiling room, as they sit around cutting up breaks. So then this guy walks in talking about artwork and it was Goldie. We had connected on all these NYC / Philly graffiti writers, since this was before he even started doing music.

CL: So I’m sure that entire experience and those connections garnered support for your gigs in London, which fed back into the success of your Philly parties. What was happening when you got back to Philly?

KB: Around the same time, after this England trip, Dozia, Josh, and our other friend Blake (he was one of Philly’s best DJs), started this party called Vagabond. What they would do is go to different clubs and change the interior, in order to build a whole new space every week. So nobody knew the location of the party until that Sunday, and we’d all get together and call the party’s phone list (before mailing lists were a thing) and share the location ahead of the party. This party went on for years, but the first iteration was going from club to club.

Northern Liberties (back in the day we called it North Philly), wasn’t really a place where people would go out. In the area there was a spot up the street called the Bank, owned by the famous restaurateur Stephen Starr, and that really started getting people into the area as far as a going out destination. There was also a private club called the Black Banana. If you’ve heard of Save The Robots in NYC, this was our version of that. Private after hours spot with all the best DJs.

Philly DJs influenced us— Philip Dickerson was one of the best DJs I’d ever heard. He only would play the gay clubs in Philly so we’d have to go to the gay clubs to hear really good house music back in the day. We’d be up in there absorbing it all. Then you’d have DJ GiGi who’s playing at Black Banana and living back and forth between NYC. He put me on to E2-E4, brought me to the Loft for the first time; these were experiences that changed my life. The last person was Tee Alford. We all went to Temple together. He was from Newark and came up with Blaze and the Burrell Brothers. He was a Sigma and played house music at all these frat parties with majority black crowds. He brought me to Zanzibar, and I met Tony Humphries, Jomanda, Ultra Nate, he would bring all these artists to Temple. Tee Alford single handedly brought house music to mainstream spaces in Philly. He’d rent out halls and it would be all age parties. We’d be seeing Jomanda and Adeva live. That’s Philly for me.

JL: I wanted to ask about Silk City. Was that your first residency?

KB: These two guys came from NYC to Philly and approached Josh and said they were looking for a DJ at their new spot called Silk City. Josh was playing at Black Banana and because of the Rave Scene he started traveling overseas for gigs, so he suggested having me there.

They gave me a chance, and it was hard because the club was still not in the best area— on the edge of madness. The sound system was horrible but I made it work. One night Dozia’s girlfriend who worked in Fashion, brought designer Betsy Johnson along with 20 other fashionable ladies to the club, and that was kind of the tipping point. Their friends told their friends and that was it. Silk City was also connected to a diner. When you sold food, you could keep a spot open 24 hours, so even though they ended that law, for the time being it helped Silk City gain momentum.

JL: Did that have anything to do with Slyk 130?

KB: No, that name came from two places. Silk City, but also when I played in Digable Planets, my name was Silkworm. A lot of silk going on [laughs].

JL: As long as I’ve known you, you’ve always had this international presence. Touring with Sade and Digable Planets, you could’ve stayed in all of these major cities— what kept you coming back to Philadelphia?

KB: You’re absolutely right. This isn’t exactly ego, but we were the kings of Philly at the time. We ran shit. We had a responsibility to keep that going. So even when I was on tour with Sade or Digable, Dozia was holding it down with our Back To Basics party. Meanwhile, I’d meet people on the road and bring them back to play in Philly. Anyone from Gilles Peterson to Jazzanova. At the same time, Josh [Wink] was bringing people like Carl Cox to his Fluid nights. We wanted to change Philly. We were always in the shadow of New York. No offense, but fuck New York! It was all about carrying the torch in Philly for us.

Once that Neo-Soul movement happened, that was it. Slyk 130 was kind of the DNA of that, but once Jill Scott came on the scene she took it to the next level, in part because they knew how to market Jill. Sylk 130 was 17 people, so they didn’t really know what to do with us or a DJ/Produced album, but with Jill it made sense. There was a movement here in Philly— just like what you’re doing in Philly, Josh! I see you doing your thing. There’s something about this city.

In 1994 I had my daughter, and our nucleus was in Philly. That was really important to me. It was the scene, it was family, it was at the intersection of Europe and LA for travel; why move if we have everything here to make our city pop?

JL: I feel the same way...

CL: Definitely!

KB: It was really hard to leave Philly. When the opportunity came to be a professor out here, I was skeptical, but once I left I knew it was time to leave. Also, I love teaching! The students have been really excited about the interviews that I’ve been doing, the archive that I’m working on and the club night on campus.

It makes me think back to my time at Temple with Tee Alford, we were all 18 years old and he was playing all of these dance records that were so inspiring. It feels like the same thing is happening with the classes that I’m teaching. These young adults are in that same age bracket and are hearing house music for the first time. I’ve been able to show them the variety of influences that goes into a DJ set and that it’s more nuanced than pulling music from the top ten charts on Beatport.

CL: Yeah it’s so important for that generation to learn about the influences!

We want to switch gears for a bit and talk about your early production. Can you touch on the Sylk 130 project and what was your goal when creating ‘When The Funk Hits The Fan’? It’s such an incredible album!

KB: First, thank you so much! I wanted to make a record that pays homage to all my heroes, musically and personally in my life. Both of my parents are on the album, my mom is on a song called “New Love” and she’s talking about her musical influences. My dad is on “Jimmy Leans Back”, because he always used to lean back in his car. This whole album is a combination of funk and jazz vocals. I always wanted to make it but wasn’t sure how to achieve that. I was on tour with Digable Planets in the 90’s, and witnessing them working on their first album, Reachin' (A New Refutation Of Time And Space), was inspiring and gave me the reassurance that I could do it.

I also needed to have someone that understood music from a perspective other than just sampling. John Wicks who founded Third Story Recording was one of my first supporters. We did the first Sylk 130 album in John’s studio. Coming off of that Digable Planets tour I had saved up some money and Josh [Wink] and I had just started Ovum Recordings. The first record we put out was “Supernatural” with Ursula Rucker.

Starting to work with artists in that way was now becoming a reality for me. Now that I had a bit of money and John was giving me a discount to use the studio, it was the perfect moment for me to work on “When The Funk Hits The Fan”. I wanted to bring the energy from the Silk City parties onto the album. We had a band and DJ coinciding, similar to what Giant Step was doing in NY, Brass in LA, The Fridge with Giles Peterson in London and UFO in Japan. All of those parties were Acid Jazz parties, with a movement of bands playing alongside DJ’s. That scene in Philly was huge and so important. All of these musicians such as Questlove, James Poyser, etc. cut their teeth at Silk City. At the party, there were these two singers that would sing over the records and band with no mic, it was so incredible. The two singers were Lady Alma and Tanja Dixon. My initial thought when I saw them was “Yoo, you have to be on this record”!

The process for making that album started with me messing with samples. Then I would go to John and he would help me expand on it. After that, the band would come in and basically translate what I had already produced. That element took the project to another level because they’re insane musicians. Also, Vikter Duplaix is on there, but he’s not singing, he plays the role of record store clerk in one of the skits.

CL: Ah, that’s so cool! We have a bunch of Vikter’s records, and have even sampled one of them for an upcoming remix. He’s so talented.

KB: He is! Vikter wasn’t singing at that time though. I put out Vik’s first record back in the day. Initially Vikter was more involved in the hip-hop scene. There was this girl named Debbie Silver that Vikter was making music with, and she introduced him to the Silk City parties and to our scene.

CL: Oh wow, we had no idea that y'all grew up together. It seems like Philly had a tight-knit scene at that time. With the variety of electronic music record labels available at that time, what inspired you and Josh Wink to start Ovum Recordings?

KB: We actually had a label before Ovum called Happy Wax. We put out a song called “Strong Song” that was inspired by Pal Joey. He was at his peak at that time, with records like “Hot Music”, “Party Time” and the “Loop-D-Loop” releases. When we were in the planning stages of Ovum Recordings, I had just had my daughter. That’s actually how the name Ovum was inspired, we looked at each release on the label as a new child. It’s kinda funny to look back on. But we started the label to give our peers in the Philly scene a platform.

Josh Wink released “Higher State of Consciousness” which was really successful! After the release of that record, Sony UK offered Josh a deal for himself. Josh was like “well, just sign the label (Ovum Recordings)— that way you would have me, King Britt and all of the music we plan on putting out”. Then Ruffhouse Records came; the label behind Lauryn Hill, The Fugees, Cypress Hill and pretty much everything 90’s Hip-Hop. They got wind of the Sony offer and were a bit surprised that we didn’t sign with them, since we already had a relationship. There was a bidding war between the two and Ruffhouse outbid Sony UK, so Sony ended up becoming our distributor for Ovum. It was the best learning experience for us because we gained insight into how corporations are structured and we had this influx of money. I had my budget to do Sylk 130, the artwork and even the remixes.

CL: There was a point with your production, where there was a shift from live/organic elements to more electronic sounds. Could you talk about where the influence for that transition came from?

KB: Well, early on I did create electronic sounding records, but it was overshadowed by the success of Sylk 130 and the live shows that I was doing. But I was always doing remixes at that time, under the alias “Scuba”. Scuba was a project that was completely electronic. The first release came out in 97’ I think? I needed an outlet for electronic stuff and went with the name Scuba. I know that there’s another artist with the name Scuba now, who puts out really good music, but I don’t produce under that alias anymore. As Scuba, I was mostly focused on remixes, and the first EP was “Where The Wild Things Are” and the cover was just Max from the children’s novel, Where The Wild Things Are. Bjork used to champion that record back in the day.

How the name Scuba came about is interesting. I was never really into taking drugs, but I did dabble back in the day. One day I took a tab of acid that my friend had and locked myself in a room for three days [laughs]. They were bringing me food, water, and whatever I needed. I only left the room to go to the bathroom. I came out of the room with that EP done. I’m not condoning drug use, but that experience had opened something in me. The reason I chose the name Scuba is because I felt like I was swimming in sound. Also Drexciya had an influence on me with the music they were putting out at that time. The early 2000’s was a pinnacle for Scuba remixes! I have to give a shout out to Alain (DJ Yellow) from France. He really loved what I was doing with the Scuba project. France at that time was special. I remember being blown away by Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk and DJ Mehdi (R.I.P.).

CL: Yes, rest in peace to DJ Mehdi. He was a huge influence on the both of us when we were starting out.

KB: It’s interesting because there was a link between France and Philly. DJ Mehdi and Diplo were pretty close, and Busy P managed DJ Mehdi. But we knew Busy P from managing Daft Punk and, of course, DJ Yellow and Bob Sinclair. We would catch Mehdi at some of our gigs because he was really into the Scuba stuff, there was definitely this admiration of each other at the time. The early 2000’s was a really powerful time for the scene. I recorded the most music I’ve ever done during that period. I was going through a divorce, so creating music was healing for me.

CL: That France and Philly connection is so interesting! We want to touch on collaboration. From your projects with Josh Wink and DJ Yellow, to your most recent with Tyshawn Sorey.

KB: Tyshawn!

CL: Is he based in Philly?

KB: Yeah he’s in Philly! He’s a professor at Penn University now. He’s one of the most important composers of our time right now. He’s created these beautiful classical compositions, but then on the other side he’s a genius drummer and jazz aficionado.

CL: How did you guys meet?

KB: There’s this group called Alarm Will Sound, they’re an orchestra based out of NYC. I had composed three pieces for them a few years ago, and they had called me again for another project. It was a three part project and Tyshawn had worked on one part. I got to St. Louis and I saw Tyshawn and I was like “damn, that’s a black conductor, that’s awesome!” He studied with Butch Morris, so his way of conducting involves different cues, which was really cool to see. We started talking and he said to me “bro, I can’t believe you’re working on this” and I was like “you know who I am?” He said “yeah I have all of your records, I love house music, I’m from Newark, NJ and I used to go to Zanzibar.” I was so shocked [laughs]!

CL: It’s funny because you were our entry point to Tyshawn. We’re familiar with your work already, but that project that you and Tyshawn released had exposed us to his world.

KB: It’s so crazy how these worlds can connect! After that initial intro, I approached him and was like “yo, why don’t we do something together”? He said “I’d be honored” and I was like “no, I’d be honored!” Also, we’re both professors. I told him that I got my budget up and wanted to fly him out to San Diego to work in the studio. This all happened three days before lockdown in 2020. Everything on that project is completely live, no edits. We did two overdubs of some percussion sounds, but that’s it. We had never played together, but we just improvised that entire recording.

CL: Wow, that synergy is incredible! Going back to collaboration. Is it important to you, and how does it inform your process when you’re creating?

KB: Collaboration for me is everything, because I’m an only child. I’ve always yearned to create with others. There’s magic in the spirit of collaboration, and I’m always learning from others. It also applies to DJing, when you go back-to-back with someone you can really learn from one another. There’s many layers to collaboration. We’re collaborating not only musically, but also culturally and we’re sharing our life experiences. Same with you, Josh and The Whooligan, you guys collaborate a lot, it’s so magical!

JL: Yeah absolutely, it’s much more than the music. Even with my partner, Silo.

KB: Ah Silo, tell him I said what up!

JL: It’s crazy because you and Josh Wink remind me of Silo and I— there are parallels there!

CL: We can see that resemblance [laughs]! A few years ago you started teaching a course called Blacktronika. Why did you decide to transition into a teaching role, and could you tell us more about the course?

KB: Wow, what a journey, man! One thing that I want to tell y'all as young people, is to stay open. Stay open to the possibilities that come your way, because you just never know! The opportunity to teach the course came at a time when I wasn’t really anticipating it. Becoming a professor was the last thing I was thinking about doing. I was just like you guys, DJing and producing.

It’s really cosmic how the story went down. So just like you guys, I was just working for myself, making music and touring. But, of course, the music business has changed, and it’s become more challenging to maintain a certain standard of living. Not saying that’s a bad thing, you just have to be more strategic with how you operate now. With that said, my aunt who used to live in San Diego passed away in 2018. I used to go out there to visit her and I would play shows in San Diego all the time, but I never really immersed myself in the scene. After she passed, I wrote down a few goals for myself. I wanted to move west, work on soundtracks, I wanted to work with young people and just for the hell of it, I put down that I wanted to live near the beach [laughs].

A few weeks later I get this phone call from my friend Alyssa and she’s like “how married are you to the east coast?” She said there was an opportunity at UCSD that she thought I’d be perfect for. My girlfriend at the time told me that I should consider it. I was so hesitant at first. I’m like “I ain’t working for the man, fuck that!” She was like “you should just fill it out so that you can see all of your achievements in one place…you have to do your CV anyway.” I was like “okay cool, for you, I’ll send it in.” I completely forgot about it, and then three weeks later I got invited to a Skype interview. I killed the interview and was invited to a few more interviews after that. A week later they said I got the job!

Here’s the thing, if you’re coming from our world, what’s missing in academia is the discussion about house, techno, drum & bass, all of these black forms of electronic music. I felt like that realization was when I knew that this is my calling, I’m supposed to be here. I told them that I wanted to start Blacktronika and they gave me the resources that I needed. The week that I was supposed to start the class, the pandemic hit. That was so crazy! I ended up constructing the class in a way that it could still be engaging on Zoom. What ended up working out is that all of the artists that I wanted to interview were at home during lockdown. I was like “Hey!” Jill Scott, Questlove, James Poyser, Goldie, everyone was home! For those that are not familiar with Blacktronika, it pays homage to all the innovators of color who have contributed to the advancement of electronic music. With this course, I not only had the students tracing the lineage of this music, but I was able to get the pioneers to come in and talk to the class. I’ve been working on an archive of interviews as well as a book called Blacktronika, Volume 1. The name Blacktronika comes from a series of parties that Charlie Dark started in 1999 in London. Those parties were geared to have DJ’s of color perform in these high art spaces.

Charlie wasn’t using the name and I asked him if I could use it, he said yes it would be honor. I had him on as my first guest of the course out of respect.

CL: Charlie’s great! Had no idea that the Blacktronika name came from him. You’re in such a unique position because you’ve actually lived through these moments in electronic music history and now get to teach it. Are you finding that your students are coming in with some knowledge of the music already, or are they totally unaware?

KB: So the first iteration of the class was only music students. The majority of them were into EDM and only a few knew about house music. The first two semesters were just music students, and there were about 40 of them. Now we are at 350 students and it’s across the whole campus, so anyone can take the class, and it’s a requirement for diversity, equity and inclusion.

CL: Wow, that influx of students is amazing! You introduce the course with Sun Ra, right?

KB: Yeah, you have to start off with the Ra [laughs]! I had Marshall Allen in class as well as different members of the Arkestra. It’s the starting point because Sun Ra was the first to incorporate electronics, within the context of Jazz. The costumes, embracing Egyptology, he is Afrofuturism.

JL: Do you think this will be something you’d want to monetize?

KB: No. I’ll do workshops and things like that, but eventually I want the archive to be free for everyone, especially for those who really need the access. Just so you know, every guest who I’ve interviewed has volunteered their time. They have not taken any money. Everyone is in for the cause, and I would not feel right monetizing it. Virgil Abloh used to pop into the class and listen. I love how Virgil always put out the resources that he had.

CL: Have you had a chance to teach the class in a nightclub?

KB: We have two clubs on campus and as a part of the course I do these club nights called Blacktronika nights, and they get packed! I would love to still teach in that club, but now the class is reaching 600 students and the capacity of the club is only 200. I would love to teach in a club, or in a space that makes sense.

CL: We noticed that Blacktronika has elements and motifs of Afrofuturism, and we were just curious to know what about these sensibilities inspire you and how did that help inform the programming at the Carnegie Hall series?

KB: On the first day of class, we define Afrofuturism and go through the lineage. It’s funny because I met Mark Dairy at Carnegie Hall the other day. Mark came up with the term Afrofuturism. But even before the term, we were all Afrofuturists. Nyota Uhora from Star Trek was the first black Afrofuturist that I had seen on screen in a major role, and that changed everything for me as an eight year old. I was always fascinated by space and the galaxy. I always looked at the stars as possibilities.

As I got older, the Afrofuturism term came out, and it brought like-minded individuals who thought like me, together. Then books like “More Brilliant Than The Sun” by Kodwo Eshun and “Afrofuturism” by Ytasha Womack came out. Fast forward to Carnegie Hall, they put together this curatorial team consisting of Reynaldo Anderson, Louis Chude-Sokei, Sheree Renée Thomas, Ytasha L. Womack, and myself. All of us have been putting in the work for Afrofuturism for many years. I did the first Afrofuturism music focused festival at MoMa PS1 in 2014. We came together and had a list of who we wanted to include. We wanted to pay respect to the elders. It was a perfect marriage because Carnegie Hall wanted to move into the future and we wanted to take over that space. One of the things about Afrofuturism is the idea of taking over a space that you don’t think is possible to take over.

CL: Do you have any thoughts on white people's place in the culture as a whole?

KB: You know, with every movement whether that be Civil Rights, Afrofuturism or Black Power, all movements have allies. Like Mark Dairy, he’s an ally. He’s a white guy, he came up with the term Afrofuturism, but he respects the culture. I embrace anyone that wants to uplift what the movement is about, but they have to be informed. But it’s really not our responsibility to provide the tools, the individual has to want to learn on their own.

Also, just to be clear, Blacktronika as a class embraces Asian and Latinx folks, as well. We’ve had Nosaj Thing, LowLeaf, I wish I could’ve had Ryuichi Sakamoto, he’s one of my favorites.

CL: Have you seen the film Coda?

KB: Yes, so good! I caught it in the movies, and I watch it every couple of months. It’s grounding. Sakamoto man, talk about next level!

CL: Thank you so much for taking out the time to chat with us! Josh, thanks loads for doing this with us.

JL: I think it’s so dope that we are sitting here talking because seeing how Craig & Brandon are moving in New York, bringing the legends out like Marcellus [Pittman] or Ron [Trent], and doing these interviews— I think a lot of our peers that are our age don’t get to have access to these conversations and so now it’s like we’re a vessel to share this insight and this information. The people that come to my parties don’t all go back home and listen to house music, and so with the music being so lost in Philly, I feel like I have to be this vessel to export this information to our community.

CL: The way we think about it is that we, for the most part, have access to the people that started this thing and that pioneered this thing, and 20-30 years from now, it will be something for the textbooks. These first hand accounts are so important for us to share, in order to get a real insight into what it was like at the inception of this music that we are so inspired by. It’s super important to sit down with people like King and document these stories. I remember when we first came to Philly, rapping with you about the responsibility we felt we had to our own city, and what we wanted to contribute to our scene. Listening to King, it sounds like there's a direct correlation from what he was doing and what you’re doing now, Josh.

KB: Thanks guys. It’s no problem at all! The work that you’re doing is so important, it’s up there with Blacktronika. Let me tell you about the scene real quick. They talk about having a seat at the table, but man fuck that, create your own table. One of the best interviews we’ve had at Blacktronika (besides Theo Parrish) was Honey Dijon. I knew Honey back in the day, and just to see her journey is really amazing. We just have to create our own spaces. Just stay true to the music and stay true to yourself, and it’ll work out.

JL: Thanks King!

CL: Thank you so much King!

“King Britt’s distinguished Blacktronika series continues the celebration of Afrofuturism in electronic music on Saturday, March 2nd, with an all-star lineup at Public Records. Kicking off the event with an early live performance, world-renowned tabla player Suphala sets forth the grooves, followed by Timmy Regisford all night long in the Sound Room. In the Atrium, London’s Charlie Dark, founder of the original Blacktronika series, joins King for an unforgettable rhythmic journey. Carozilla rounds out the night UPSTAIRS with her rare selection of sonic gems. Grab tickets below.”

King Britt presents Blacktronika With Special Guests Suphala, Timmy Regisford, Charlie Dark, and Carozilla

7PM | Public Records